An Evening with Syren Nagakyrie from Disabled Hikers

A recording of our discussion about Syren's book "The Disabled Hiker's Guide to Western Washington and Oregon

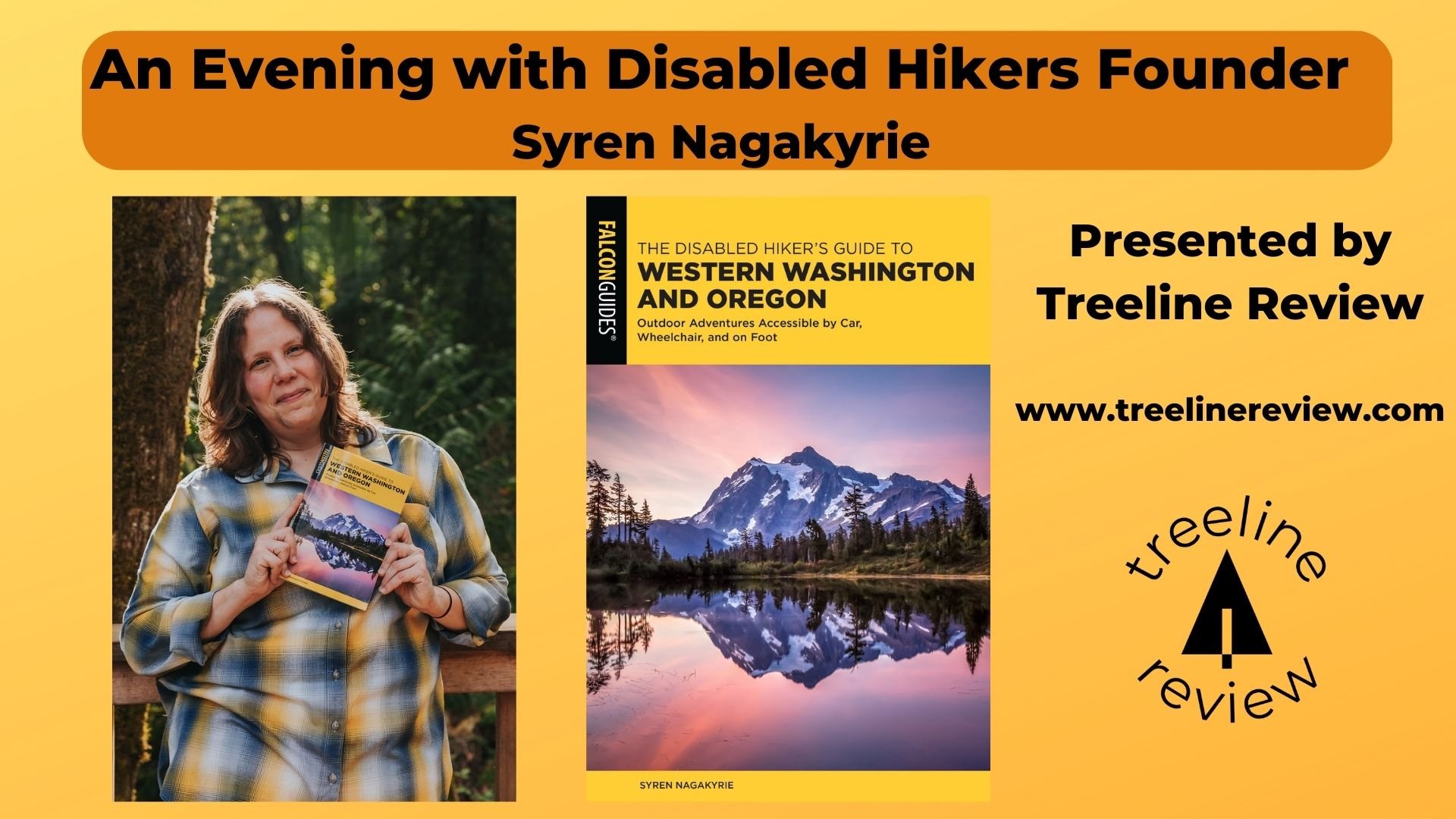

Syren Nagakyrie (they/them) is founder of Disabled Hikers and author of The Disabled Hikers Guidebook to Western Washington and Oregon ( REI | Amazon | Bookshop.org )

In this new guidebook, you can learn about outdoor adventures accessible by Car, Wheelchair, and on Foot.

Disabled Hikers is an entirely disabled-led organization. It celebrates disabled people's experiences in the outdoors.

Video recording of syren’s talk and interview

Note: this video has been edited for length and clarity.

A video recording of a presentation by Syren Nagakyrie, founder of Disabled Hikers

Transcript

Note: this transcript reflects the video, which has been edited for length and clarity, for those who are unable to watch the video.

Liz Thomas (Treeline Review): Welcome to an evening with Disabled Hikers founder Syren Nagakyrie presented by Treeline Review. My name is Liz Thomas. I am co-founder of Treeline Review along with Naomi Hudetz, who is also here and will be helping with Q&A at the end of this event. Please feel free to introduce yourself in the chat and where you're calling in from.

Treeline Review is a gear review website that makes gear reviews for the rest of us, those of us who haven't seen ourselves reflected in traditional outdoor media. We build inclusive and beginner-friendly outdoor gear stories that focus on representation and being better stewards of this planet.

One thing that makes us a little bit different [than other gear review sites] is we're objective. We have no ads. We're 100% reader-supported. We're not sponsored by gear companies. That means to help continue our mission, when you purchase items online through links on our website, at no additional cost to you, it helps support our mission. So when you decide to purchase Syren's book after hearing this wonderful talk, you can find a link to bookshop.org or REI or one of the many other book retailers that sell Syren's book. Consider using one of our links to do that to support both of our good work.

Before we start, we want to let you know we will be recording this webinar so that we can show share Syren's talk with those of us who were unable to make it and so many people wrote in and said, "Oh, we're so excited about this!" That's something we're very excited to be able to do.

Without further ado, I'd like to introduce Syren Nagakyrie, a longtime disabled activist and community builder who is committed to an outdoors culture transformed by fair representation, accessibility and justice for people who are often marginalized outdoors. They are the author of The Disabled Hikers Guide to Washington and Oregon: outdoor adventures accessible by car, wheelchair and foot by Falcon Press.

We'd like to ask if you have questions during the event, please save them until the end. There will be time at the end after the talk, where we will be asking questions. We'll also be utilizing the chat during that time as well. Thank you so much. And we're very, very lucky to have Syren here.

Syren Nagakyrie (main speaker): Thank you. I'm really excited to be here. Thanks for hosting and building this space for us to come together and talk a little bit. I am the founder of Disabled Hikers. Thank you again for being here this evening and sharing some time with us. I'm really excited to be here. I am calling in from the traditional lands of the Quileute Nation, which is Forks, Washington on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington state.

A little bit about accessibility in this presentation. I will try to describe everything that is shown on the slides and read the content of the slides. We'll be talking about my background, how I got started, and the formation of Disabled Hikers. Then [we'll] be going into the book and how to provide accessible trail information for folks and what that information looks like, specifically within the context of the book, but also how you can provide that to your communities as well.

Again, I'm Syren Nagakyrie. I use they/them pronouns. I am a white, queer, non binary person with multiple disabilities and chronic illnesses. Here on the right, there's a photo of me with my little dog, Benji, who is a very important part of my life. We're standing on an overlook outside of Leavenworth, Washington. The golden larches are in the background.

This was a really meaningful moment for me, because, for me, nature has given me a real sense of belonging. For so much of my life, I felt very excluded from society, from my peers, and from the outdoors in general. I went through a lot of periods of my life where I was experiencing chronic illness and symptoms of my disabilities. I just wasn't really able to go out and be with my peers and do the type of typical childlike activities that [other] people did. I also grew up pretty poor and with disabled parents, so I didn't really have the opportunity to go out and do things like camping or road trips or summer vacations or things like that.

But what I was able to do and did a lot of was just hanging out in my yard during the day, and really just paying attention to the plants and the flowers and the birds and the bugs that surrounded me every day. Watching those experiences and the variety of ways that bodies and forms exist in nature informed my experience and the way that I view and experience my own disability.

“Watching ...the variety of ways that bodies and forms exist in nature informed my experience and the way that I view and experience my own disability. ”

[I was informed] in seeing the ways that nature adapts to various circumstances and the ways that people go out and seek out what is considered "unusual" in nature. We see these examples of disability of genetic difference. These are the things that people tend to want to seek out and find to be incredible. Experiencing that on the one hand, but then also experiencing, on the other that disability can be so shunned, was really informative for me.

I often go outside to really lean into and brace against nature and see a lot of this reflected back to me--having a place to feel more comfort when I'm having these experiences of illness and disability and trauma.

“I often go outside to really lean into and brace against nature and see a lot of this reflected back to me—having a place to feel more comfort when I’m having these experiences of illness and disability and trauma. ”

Seeing all of that reflected back to me, especially as the climate crisis accelerates, and the environment itself becomes increasingly disabled, having that kind of reciprocal relationship, I feel like it can help inform us as people who are outdoor enthusiasts who are caring about the environment, who want to address climate change, and these issues.

Seeing that reciprocal engagement is important. Not only, for example, do more people become disabled, as the climate crisis continues, more people experience an exacerbation of disability. We're also seeing these experiences of disability in landscape and also the ways that we all adapt and overcome that in various forms. I feel like there's so much that is wrapped up in disability and the landscape. Exploring that is important.

As I mentioned, I felt really excluded from a lot of my peers growing up. I wasn't able to do things like go out for camping trips. But I did try Girl Scouts. Of course, I had physical education requirements in school, like a lot of us had, and just kept encountering all of these negative experiences and perceptions about me and disability as I was growing up. I was often just told, like, "Oh, you can just stay behind. Just sit this one out. It's okay. You won't be penalized for it. But just stay over here and out of the way." That continued throughout a lot of my life.

As I entered Community College in the early to mid aughts, I enrolled in a few natural science courses, because, again, I was interested in learning more about the natural world and what these experiences meant for me. So I enrolled in this class and had the opportunity for the first time in my life to get out of Florida and go experience a brand new landscape, which was the Grand Canyon.

We were out on this trip with a big group of my classmates. We were here-- this is a photo looking down into the entrance to a cave. It's kind of hard to see, but there's quite a bit of snow on the ground on the rocks. There's a couple of people who are on the rocks climbing down into this cave. We're there and everyone's excited and having a good time and excited to have this new experience. We get to this place and the teacher [says], "All right, let's go down into this cave." Obviously, I can't do this. This is not something that I'm able to do. So the professor [says], "Well, I don't know what to tell you. Just sit here and wait for us to get back." I was like, "Okay." I just sit there and hang out while everyone else went and did this activity.

But in that moment, I was just sitting there, basically alone in the desert and sitting on this rock and looking around me in this totally unknown landscape to me. It was a tense moment of feeling excluded, but also having this moment of quiet to just lean into that experience and what it meant --really paying attention to the landscape and everything that surrounded me. It was a really meaningful experience.

Later on, I was talking with my classmates about what they experienced through all of that. Basically, they really didn't have anything meaningful to share about the experience. They all talked about having a good time together. But as far as what they learned, or how they connected with the environment, they didn't really have anything meaningful about that. So that was one of the first times I realized that the slower way of being in the outdoors, was also incredibly meaningful.

As I continued leaning into those experiences, and wanting to find more ways to be able to enjoy the outdoors, and something that was meaningful for me, I enrolled in an herbal school program in 2008-ish. I moved to western North Carolina for this two-year program. It was the first opportunity I had to connect with people and plants in a meaningful way in these kinds of slower experiences. If you've ever been on a plant walk, you know that it can be a very slow experience. Everyone is hanging out, nerding out on plants, traveling a short distance. That was my first time being in that kind of environment and situation.

At the same time, I was still very often told, "If you can't do this, it's okay. You can stay behind. Don't worry about it." I would ask for information about the hikes that we would be doing and where we should be going and the conditions. I just wasn't receiving any real support or information. So I was still experiencing those challenges.

But definitely, it was the first opportunity, I had to try to find a sense of belonging, and start figuring out on my own what it meant to engage with the outdoors and with nature.

Here on the right, there's a photo of me kneeling down in this huge patch of St. John's wort, which is a beautiful yellow flower that grows on the open hillsides. It was a moment that allowed me to accept who I was and how I experienced the outdoors.

Fast forward a decade or so. In late 2017, I moved to the Olympic Peninsula and Northwest Washington state. It's an incredible area: Olympic National Park and National Forest. There's old growth rainforest and rocky coastlines and mountains, and a little bit of everything that you could ask for in an environment.

I was excited to start experiencing this and go out and having these new experiences and figure out what it meant for me. So I started doing lots of trail research and figuring out where I could go and what that looked like.

One day, I started out in the Quinault rainforest, and started a new segment of a trail system that I had done before, but I hadn't done this particular segment yet.

Again, I've done tons of research about it to make sure it was something I thought I would be able to do.

I immediately got out there and encountered tons of obstacles and barriers, like steep drop offs, and rocky slopes, and steep stairs, and all of these things that weren't included in anything that I read anywhere. It was kind of a dangerous situation for me. I was having to continue along because it would have been just as difficult to turn back. So I just kept going.

I was increasingly getting in pain and fatigued and frustrated. Finally, I ended at this bridge over a waterfall that you see here on the right. I was standing there leaning against this bridge and just feeling exhausted and in pain and so frustrated. But in that moment, inspiration struck. I said, "Why don't I do something about this?" I went home and wrote up a quick blog post and trail guide about my experience there and put it up on a quick WordPress blog. Disabled Hikers trail guides and Disabled Hikers was born from there.

We almost immediately started getting traction. We were getting media mentions and all of that pretty much right away, which I was mentally not prepared for but was pretty excited about. From there, through the blog, the social media community started doing group hikes. It has blossomed in ways that I never expected.

There's a quote that says there is no one right way for water to flow. There's no one right way for my body to be, either. For me, it's about the ways that nature resists these binaries and restricts categorizations. The idea that there's only one right way to do or to be--nature isn't like that, and neither are our bodies, and neither should we expect each other to be. There's a myriad of ways for water to flow. Sometimes it overflows, sometimes it's in a drought, sometimes it flows north, sometimes south, sometimes low, sometimes fast. And it's all okay and acceptable.

So Disabled Hikers, what do we do? On the left hand side here, there's a drawing that features three disabled folks in the outdoor environment. Our mission is to build disability communities and justice in the outdoors with a vision of an outdoors culture transformed by access, representation, and justice, for disabled and all other historically marginalized people.

We do a lot of work in the community. We do a lot of advocacy, create a lot of resources, events, trainings, consultations. We work with a variety of parks and other outdoor organizations to help increase access and inclusion for disabled folks. We work with a lot of brands. We have a broad variety of things that we do.

And we're going to be expanding to include a Disabled Hikers network and leadership development programs, starting to do more group hikes, and all of that. We're excited about where we're going. At the core of it all is community.

Here, there's three photos of a variety of groups of folks from some of our group hikes. For us, it is that being a community-led piece--that the resources and the things that we provide are by and for disabled folks. It's flipping the common narrative that we find in a lot of disability service organizations in that it's non disabled people doing things for disabled people. We really flip that for us.

“It is disabled folks that are the experts. We are the leaders. We are perfectly capable of figuring these things out for and with each other. We don’t always need non disabled folks to lead the way and show us how it’s done. It’s about that empowerment and autonomy and respecting the broad variety of experiences of disability. ”

It is disabled folks that are the experts. We are the leaders. We are perfectly capable of figuring these things out for and with each other. We don't always need non disabled folks to lead the way and show us how it's done. It's about that empowerment and autonomy and respecting the broad variety of experiences of disability.

So the book, how did we get here?

It was one of those kind of like coincidental synchronous things., I was in an article about Disabled Hikers in Outside Magazine and someone from Falcon Guides read that. At the end, I had mentioned, "I'm writing these trail guides. I would love to write a book one day. I've been a writer for a long time. I've been writing since I was a kid." And someone from Falcon saw that and reached out to me and said, we'd love to work with you on that.

So I said, "Well, I said someday, I didn't mean right now. But you know, all right, cool. Let's do it." So, here we are.

On the left here, there's a cover photo of the Disabled Hikers guide to Western Washington and Oregon: outdoor adventures accessible by car wheelchair and foot. The photo is by Scott Kranz. It's of Mount Shuksan with Picture Lake in the foreground.

It is very much a groundbreaking book. It's the first book that I know of that's been written by a disabled person for the broad variety of disabled folks. It includes scenic drives and wheelchair accessible trails, wheelchair hike-able trails, foot trails that are suitable for disabled folks. And it utilizes a rating system and really detailed trail information, which we'll talk about a little more.

Every trail in this book has been personally assessed by me. I've done tons of research, gone out and hiked every trail, and done all the physical assessments to create these very detailed guides.

So about the process: writing this book was a two year process. I signed the contract, I guess it was January of 2020. And then, as we all know, three months later, the world changed. We entered the pandemic. Then there were record breaking wildfires and snowstorms. That was definitely unexpected and complicated a lot of the process. But, we got there. It was very much a two-year fellowship diving into the lack of accessibility that is out there-- not only in the trails, but in the information that is available, how people understand disability, and accessibility and the outdoors.

On the left here, I like to show this photo: It's a screenshot of a Google map with a bunch of color-coded different icons representing different types and things like that on the trail. This is just a small snapshot of the process of trying to find all this information and organize it in a way that makes sense.

Guidebooks need to be written in a certain way, with a broad enough variety, and trails dispersed in a variety of locations. Finding all that fits within the guidelines was definitely a huge challenge. I think I probably hiked over 150 trails in the process of writing this book.

It starts with tons of research. Every trail probably requires two to three hours of research, trying to track down as much information about that trail as possible so that, first, I can decide whether or not it's something I can do. And then, whether or not it will be something that would be suitable for the book to create a resource about. But then, I still have to go out and hike it and do the assessment. Of the trails I hiked, a good half of them still end up being not as accessible as I thought they were going to be based on the research.

Then, of those [trails], still only maybe half of those are suitable to include in a guidebook. So it's definitely not as simple as a typical guidebook. There's a lot more involved research and planning and [work] in the hiking process.

Creating something new, what I encountered along the way: on the right hand side here, there's a photo of me pointing at a trail map for the Icicle Gorge Trail. What I ultimately realized through the process of writing this was that I needed the thing that I was creating, to be able to create the thing.

That's been something that has been true for a lot of the work that I've done. Trying to create something that you need to exist in the world is both a meaningful thing and a very challenging thing.

Figuring out how much bad information is out there and how much confusion and lack of awareness there was out there about accessibility was eye opening to me in a lot of ways.

I wanted to share a couple of examples of the kinds of things that I encountered while doing some of this research. A couple of trail examples here:

Cape Flattery: On the left is a photo with a multiple-step boardwalk with some stairs. This trail is on the Makah land. It's the most Northwest point of the contiguous United States. And it's noted as easy pretty much everywhere that you look. But it has 200 feet of elevation change and near 100 steps in three quarters of a mile, which is not easy for anyone who has mobility or balance or respiratory issues or even just bad knees. Then to actually get to the view that everyone talks about, you have to climb up a steep ladder to this platform or step to the very edge of the cliff, which is not accessible for a lot of folks either.

Marymere Falls: also in Olympic National Park at Lake crescent. This one is often sometimes kind of ridiculed as a tourist and family friendly trail, which means, "Oh, it's not worth it for any 'real hiker,'" which, of course I disagree with. The trail is really not that easy at all. There is a short portion that people consider accessible but it still can be pretty difficult, especially if you don't have an adaptive wheelchair. Then the rest of the trail that actually gets to the waterfall gains over 250 feet in less than half a mile and there's over 120 stairs. So that's definitely not easy for me and a lot of folks.

So what is it that makes this book unique? And what kind of information do we cover? Again, it's very much about providing that detailed, clear information, being as detailed as possible.

I mentioned earlier the unique rating that is in the book that I created. I call this the spoon rating. It's based on Spoon Theory, which is kind of a symbol or metaphor created by Christine Miserandino. In short, it's a metaphor. She starts with a certain number of spoons and discusses the amount of spoons-- or energy--that every activity requires to get through the day. This is a very well known part of disability culture.

I wanted to take an aspect of disability culture and apply that to this resource so that it would be meaningful to more folks and to provide an objective and specific rating for a trail. It combines both a "difficulty rating" with accessibility and a quality rating and tries to do that in a much more objective way.

“I wanted to take an aspect of disability culture and apply that to this resource so that it would be meaningful to more folks and to provide an objective and specific rating for a trail. ”

[For example:] We start here [on this hike] with two spoons. It's zero to two miles, level, and even with grades under 8% paved, very easy to navigate, probably wheelchair accessible. [Another hike that is] two spoons: one to three miles, short grades, 12% firm and paved surface with no obstacles. Access takes a little planning, probably wheelchair hike-able. Three spoons is two to four miles. Generally gentle elevation changes, short grades up to 20%, firm surface, minimal obstacles, possibly wheelchair hike-able. Four spoons is three to five miles, prolonged grades of 10 to 15%, elevation changes over 500 feet or longer than half a mile. Obstacles require advanced planning or basic trail map reading. Five spoons: five plus miles, prolonged grades 15 to 20%, elevation changes of1000 feet or longer than one mile trail. It has many obstacles and requires extensive planning or navigation.

Now, within these ratings any one of these factors can shift and it may not change the overall rating. Here, for example, a short grade is anything less than 30 feet and prolonged grade is anything over 30 feet, 100 feet and then trying to parse out being very specific about what wheelchair accessible and wheelchair hike-able means.

Wheelchair accessible trails have very specific guidelines about what that means. So trails that meet all of those are defined as specifically wheelchair accessible trails. But then there's lots of different types of wheelchairs and wheelchair users have a variety of experience levels and comfort levels, and access to equipment. All of that still influences how accessible a trail may be for someone.

A trail may still be wheelchair hike-able if [a hiker] has adaptive equipment or if they are an experienced wheelchair hiker. Including all of that information in there is important, too.

With Marymere Falls, there's an explanation of how I wrote about this as opposed to what is very common [for guidebook writers]...I rated it as two spoons for the first half mile, which is wheelchair hike-able and gains under 100 feet in elevation. The surface is compact earth and gravel, but there are two areas of incline and uneven ground that may be difficult.

Then, the hike description goes into more detail about that. Then, it's five spoons for the complete hike to the falls, which is the most difficult. It gains 250 plus feet in less than half a mile. Then, I talk about the max grade for each section of trail, what they'll encounter along the way. The actual hiking guide goes into all of this in much more detail.

Here's another example, Happy Creek Nature Trail. This is located on Washington Highway 20 in the North Cascades. This is a trail that's often overlooked as being kind of "not worth it." It is a short boardwalk that's located right off the highway. But it is fully wheelchair accessible and it's lovely. There's lots of places to sit and enjoy the babbling creek. There's some old growth forest.

It also is the access point to a longer, more difficult trail. So people who do start here often just kind of continue on to that more difficult trail and don't take the time to enjoy this short Boardwalk. So it is very accessible. But then, here on the right in the description, there's some description about the parking lot, and the accessible parking there.

“What often happened was even on these accessible trails, there may be a lack of truly accessible parking.”

What often happened was even on these accessible trails, there may be a lack of truly accessible parking. There's a couple of accessible parking spots here. They do not have the striped access aisles that allow for someone using a wheelchair to load and offload. So, I give information about possibly being able to use the right parking spot, which has enough space in front of the toilets, or there's a long parallel spot that you could offload basically into the driveway, which is less than ideal. But providing those kinds of options and information is important.

June Lake: This is another example located in Washington State near Mount St. Helens. It is an "easier" portion of a trail that is the access point to a longer, more difficult backpacking trail that loops around the mountain. So again, people will often use this to access that backpacking trail but they don't share information about this shorter section of the trail that is easier and more accessible for a lot of folks. And it still ends at this beautiful lake with a waterfall that tumbles down basalt cliffs. It has a nice little picnic spot. There's even a nice little, fairly easy backcountry camping opportunity for folks. Tthings like this where there are portions of the trail that may be more accessible, it's important to provide that information as well.

The Discovery Park loop: this is in Discovery Park in Seattle. It's an urban park. A lot of people dismiss city parks as not being worth it or just kind of that place you go to real quickly after work. They don't see them as necessarily valuable in and of themselves. But also a lot of folks assume that city parks are all very accessible and easy for everyone to access and that's also not true.

The main Discovery Park Loop Trail is rated as three spoons. There's some difficult areas there. Within the park, there is no designated wheelchair accessible trail anywhere in the park. But they do offer some accommodations around being able to book a shuttle or get a pass to drive down to the beach that can be more accessible for folks. Again, there's limited options there as well.

[By] going into a little more detail about the trail information that is in the book, hopefully, this inspires you to think about trails a little differently, and how to provide this information to people and the kind of information that you should be looking for.

There's the trail type. This can be an out and back. That's when you go out one way and travel back in the same direction. Or there's a loop when you travel in the same direction one way. There's often a lot of discussion within the hiking community about whether out and backs or loops are better. Personally, for me, I prefer out and backs because I know what to expect on the way back and I can kind of relax into the experience a little more. Plus, it's always different to see it from a different angle.

Then the distance: the entire length in miles for the trail. If it's an out and back, [that means] how long is it to get there and back. But also, what distances could you go and turn around and still have a good experience?

[Then] we provide the starting elevation and the total elevation gain. Also, when possible, the elevation loss. Sometimes, depending on what app you're using, that can be more difficult to capture. But, providing both the total gain and where that gain happens [is important]. There's a big difference between gaining 500 feet in half a mile or 500 feet vs. two miles. So I'm very clear about what that means by including that Max grade, which means that steeper section of the trail that's longer than five feet.

That can make a big difference for folks--not only people who use wheelchairs need to know whether their wheelchair will be able to navigate that. But also anyone who uses mobility equipment who needs to consider that information

Max cross slope: This is the steepness of the trail on the horizontal axis or from the inside to the outside, or vice versa. This is often left out, but it's important for folks who use wheelchairs, anyone who has an unsteady gait, anyone who uses mobility equipment, anyone with difference in limb length--all of that can really make a trail with a steep crossover can be difficult to travel on. It's important to measure that as well.

The typical width of the path: that is a factor for wheelchair users. Again, there's a variety of types of wheelchairs out there. The minimum requirement for a wheelchair is 32 to 36 inches, but there's a lot of adaptive chairs out there that need a much wider area and also adaptive bikes need a much wider path. Walking on a narrow trail can be difficult, especially if you have any mobility challenges, so that's important to know.

The typical surface: this is also referred to as the tread of the trail. It could be natural, it could be paved, it could be gravel, it could be rock, any combination of that. That's important to know. It also feeds into obstacles and and how firm that surface is going to be, whether it's going to be something that is muddy, or something that is slippery– all of that is important to know.

Then trail users: this can be other hikers, runners, bikers, horseback riders. I think sometimes people kind of overlook this, but it is important to know for me. I need to know if I'm going to be sharing that trail with a mountain biker who is traveling much faster than I am. I may not be able to get out of the way quickly enough for a bike who's coming quickly down a trail. Having that information up front so I can decide if it's something that I want to deal with that day is important.

Season/schedule: when's the best or safest time to experience the trail. What kind of water is available? That includes, if there's water fountains, if there's places to fill a water bottle, or if it's surface water that needs to be filtered or treated. Knowing whether or not water is available is important to me, even on just a short day hike that's a couple of miles long. With my disabilities, I have to keep very hydrated, and I'm unable to carry enough water often to to really meet that need, so knowing whether or not I'll have access to water is important.

Knowing if there's restrooms and benches. Benches along a trail are important. Any place to sit down, picnic tables.

Dog friendly: Of course, service animals are allowed anywhere on any trail unless the land manager has specifically done a study to say that it would be too damaging or too much of an imposition on the environment. But other than that, which is an intensive process, service animals are allowed anywhere and everywhere that their handlers are. So [service animals] aside, [this covers] knowing whether or not pets are allowed, and whether it's appropriate for pets to go. There are lots of trails that they are allowed, but may not be the best idea for a variety of reasons. So that's important.

Cell reception: A lot of people have this idea that you go into the wilderness to disconnect, but for me, I need to know whether or not I'm going to have access to a cell phone if I run into issues. So that's important.

Being clear about passes and entry fees. I know that can be very confusing depending on where you are.

Being clear about how to find that trailhead. That includes directions there. And then once you're in the parking lot, exactly orienting someone to find that trailhead and where they can find the information and a map and things like that

Of course, land acknowledgments are incredibly important. The book includes thorough land acknowledgments. All of my intro material includes information, so being intentful and meaningful about that is important.

The hike: this is a really detailed trail description for the entire length of the trail that covers all of the above information more. It's very much a step by step or roll-by-roll guide. I feel like people sometimes think if I give all of the information about this trail, it's going to ruin the experience for someone. But it really doesn't. It helps me prepare more, so that I can lean into the experience more and actually enjoy it.

Whenever possible, in this book, I've included detailed maps and elevation profiles. I remember elevation profiles used to be included in a lot of guide books, and they don't include them often anymore. But I told them, it was very important for it to be in this book. So they are there and there's information in there about how to use elevation profiles. But in short, they're kind of like a graph that shows the elevation at any point on the trail. It's not an exact replica of the elevation of the trail. But it does kind of give you a general idea of what the steepness and the grade will be.

I hope that this guide helps everyone to get out there and enjoy the outdoors, whether you're driving or wheeling, or hiking, or scrolling, or just sitting on a park bench. There's lots of things in here that are just nice places for a picnic or to go hang out. It's all valid and important. Everyone belongs outdoors.

I hope that through these experiences of sharing access and disabled perspectives that we can help shift more of this outdoor culture.

Thank you. You can find more on the website at disabledhikers.com. You can reach me at Syren at disabledhikers.com. And we are on Facebook and Instagram at @disabledhikers. Please follow us if you don't. We've got 15 minutes or so for questions.

Naomi Hudetz (Treeline Review): All right. Thank you so much, Syren. That was wonderful. We've gotten some great questions and comments in the chat. [Here's a question] "What is the difference between wheelchair accessible and wheelchair hike-able?"

Syren Nagakyrie (main speaker): Yeah, the wheelchair accessible has really clear guidelines specifically. The Americans with Disabilities Act actually doesn't cover trails, specifically. The Architectural Barriers Act does, which technically only applies to Federal funded lands. That's kind of a tangent, but those guidelines are there to be able to compare to so a wheelchair accessible trail will meet all of those guidelines, such as being paved, firm, grades under, generally five to 8%.

Then wheelchair hike-able trails perhaps, for example, may have a steeper grade or an unpaved surface, some rock, some obstacles, things like that. But if you are using an adapted wheelchair, or an experienced wheelchair hiker, it can still be accessible to you. Some of how to know the difference is a little bit of, you know, just experience and talking with the community and some subjectivity to that. But I do think it is important to understand that there are a broad variety of wheelchair users who are also hikers, and what that means for folks.

Naomi Hudetz (Treeline Review): One more question about the whole spoons rating. Could you explain the history of that and what that means?

Syren Nagakyrie (main speaker): Yeah, so The Spoon Theory, by Christine Miserandino, you can Google that and read her article about it. I probably won't describe it as as well as the full article. But it is this idea that a lot of folks who are disabled or chronically ill have to ration their energy throughout the day. For example, [if you] start the day with 10 spoons. Svery activity that I do requires a certain number of spoons. Getting up and getting dressed, that's two spoons. Going to work: that's five spoons. Cooking a meal: that's two spoons. So taking that idea of this symbol for disability and chronic illness, which has become an important part of disability culture. You say "Spoon Theory" in a room full of disabled chronically ill folks and everyone's like, "Oh, yeah! I'm low on spoons today." Taking that idea and applying it to a "difficulty rating" or an accessibility rating. For example, the easiest hike may only require one spoon of your energy for the day. A more difficult hike will require three to five spoons of your energy for the day. I hope that clarifies a little bit.

Naomi Hudetz (Treeline Review): [Another question for the audience] How about any recommendations for finding out how accessible an area is? is when you're planning a vacation, the national parks for example.

Syren Nagakyrie (main speaker): Yeah, it can definitely be a challenge. The National Parks Service does have an accessibility section on their website. Unfortunately, it's not really standardized. Every park has different information and different quality of information. But if you are on the national park webpage, there's always a thing, I think it's under Plan your visits, and then accessibility, and you'll be able to find some accessibility information on there.

But honestly, just doing a ton of Googling, and [googling] "this national park accessibility," and then reading things like guides from, for example, trail associations will often have some information. Reading other blogs and joining local Facebook groups, and asking for information there. It's all some steps you can take.

Naomi Hudetz (Treeline Review): [Reads a question from the audience] Did you consider including other kinds of disabilities, such as neuro divergence and people with sensory needs, such as light and sound? For example, how loud a trail is? Or how much light exposure there is?

Syren Nagakyrie (main speaker): Yeah, absolutely. I'm neurodivergent myself. I always try to include that information. I think, probably for sure, I could have done a little better job of it with this book. And I'm planning on doing that in the next book for Northern California. So I'll be a little more specific about that. But for sure, there's information about, for example, being clear about any places where you may get confused or lost. Noting if there's any loud or potential for loud or unexpected noises, like trains or anything like that. So there's some information in there about that.

Naomi Hudetz (Treeline Review): Good. That's good to hear. Someone also mentioned that the wider trails are good for people with PTSD. That's helpful information as well.

Syren Nagakyrie (main speaker): Yeah, and knowing where the spots are, where you can step off trail and get off of the main trail and where to sit and things like that.

Naomi Hudetz (Treeline Review): [Reads a question from the audience] Where can you buy the Southwest Washington, Oregon guide? I assume it's Amazon. All major retailers?

Yep. Yeah. Anywhere books are sold. I know there's a link to it here on on the event with Treeine Review. You can get it on our website. It should be more available in bookstores now. It did initially sell out within the first two weeks of being released. But a second printing is done. So it should be out there now. Hopefully.

Naomi Hudetz (Treeline Review): Do you know if libraries usually stock books like that?

Yeah, actually, there's been a lot of interest from libraries, which made me really happy. I'm a big library nerd. Yeah, a lot of libraries around here have copies.

Naomi Hudetz (Treeline Review): Good. I'm glad to hear that.

Syren Nagakyrie (main speaker): Oh, and there is also a Kindle version too. Of course, that enables, Kindle Audio Reading.

Naomi Hudetz (Treeline Review): [Reads a question from the audience] Here's another one. I'm curious if any parks reached out, or if there was any collaboration towards making better accessibility, such as better parking, while you did the research, or after the book came out?

Syren Nagakyrie (main speaker): I have definitely worked with a lot of parks throughout this whole process. I think there's probably been a little more interest since the book was published, which is to be expected. For example, like I worked with the Olympic National Park to create trail guides for all of their front country trails. That's up on the website. I have lots of meetings with various parks and things like that, to improve access.

Naomi Hudetz (Treeline Review): Are you planning a guide for Eastern Washington?

Syren Nagakyrie (main speaker): Yes, hopefully, one day. I'm working on Northern California right now. Then, we'll see what comes next. Each guide takes me easily one to two years to write. There's only so many I can do at a time. But we are hoping to, again, to do this training and leadership development program to train more folks on doing this so that they have the opportunities to write more guides for their areas.

Naomi Hudetz (Treeline Review): And I believe you said Northern California is also possibility, right? Yeah, I'm working on Northern California now. That should be out spring 2024.

Naomi Hudetz (Treeline Review): [Reads a question/comment from the audience] I love the mention of the benches on the trails. It's so important for so many people. Do you also mention rocks that can be used to sit on and rest as many people can't sit on the ground and get back up?

Syren Nagakyrie (main speaker): Yeah, nice rocks, nice logs, trees to sit on. Anywhere that I can take a seat.

Naomi Hudetz (Treeline Review): [Reads a question from the audience] Do you have plans to involve more perspectives across the country for other areas too?

Yeah, we're working on the the Disabled Hikers network and the leadership development program, which will be an opportunity for folks from everywhere to come together and learn and share information and develop more leadership. We have our social media, Instagram, we have a Facebook group. All of those are good ways to connect with other people, too.

Naomi Hudetz (Treeline Review): [Reads a question from the audience] Can you talk more about the trainings?

Syren Nagakyrie (main speaker): Yeah, we're still working on it. We're working on creating them. I'd say follow us online and sign up for the newsletter to stay up to date. We'll be offering a variety of opportunities, training opportunities that will start with creating a variety of multiple accessible ways to do these trail assessments and reviews for a variety of disabled folks to be able to do that. Teaching how to do the trail assessments, how to write guides, how to do the advocacy work, how to work with parks, and organizations and all of that, so that, yes, more folks can do this in their communities.

Liz Thomas (Treeline Review): We're right at six o'clock PM. Thank you so much, Syren. Thank you, everyone, for being part of this event. It was so great to have you here and to learn more about the book.

Just as a reminder, everyone, go out and get a copy of Syren's book while they're available as part of the second printing. We'll also have this available as a recording as well for those of you who are unable to attend or who have friends who you think would be interested in seeing this talk. Thank you so much, everyone. Thank you!